When I was eighteen, standing in a corner suite of the Windsor Hotel visiting my first Spring1883, I was asked by an awkward acquaintance, “why do you bother drawing the way you do when you could just take a photo?” It would be cool if this talk could be some kind of answer to that question. But also as I felt at the time and now—why does anyone make the way they do? Is it not like breathing or walking?

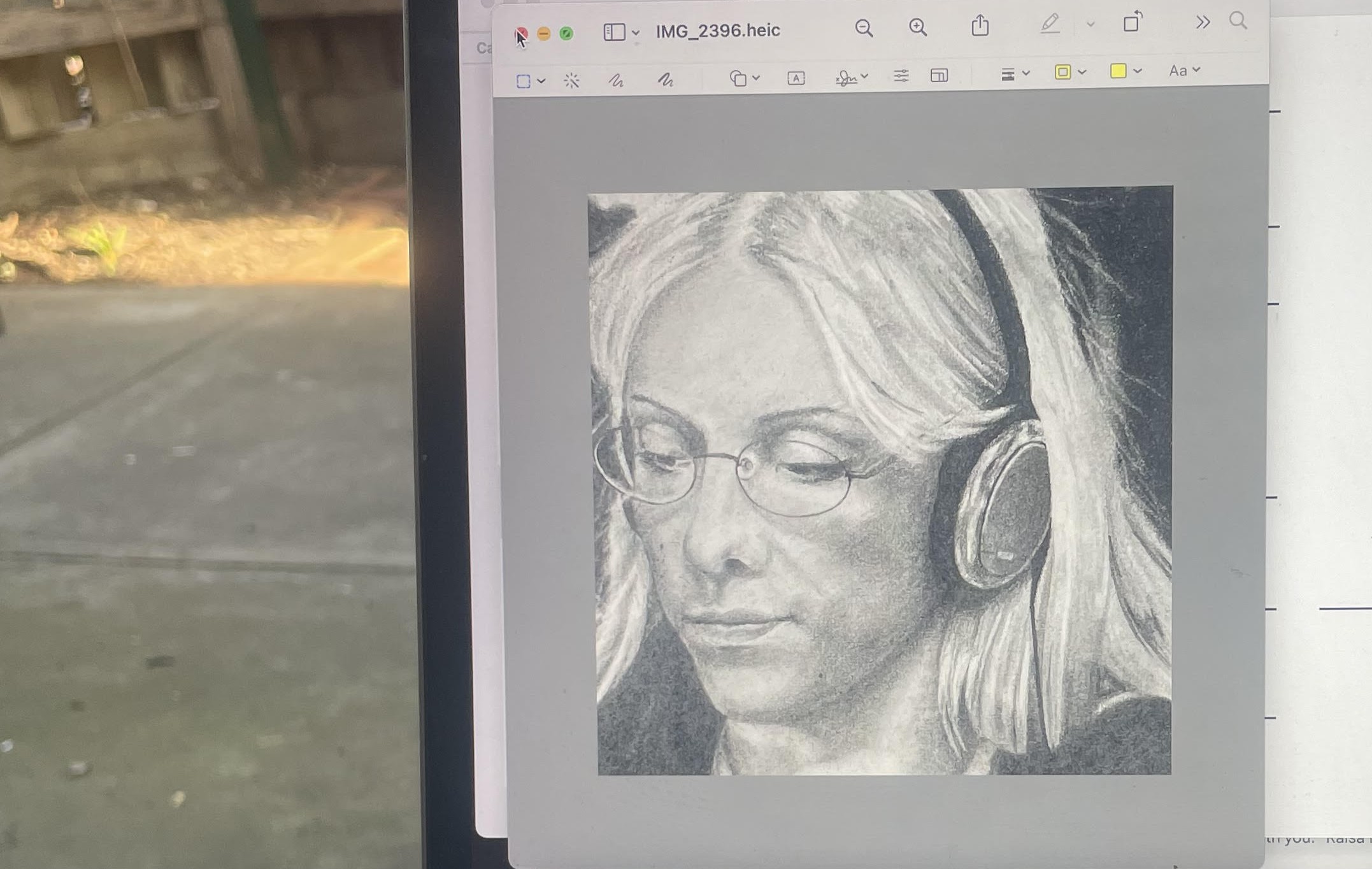

I took a year and a half off drawing in my third year of undergrad and the first half of my honours year. Feeling artistically lost and frustrated by the limitations of the drawings I was doing — tiny, realist translations of photos I was taking to memorialise my late adolescence. Tiny drawings that no one at art school really had anything to say about except how pretty they were, and that they didn't know “how I did them”. When talking to Amelia Winata for MEMO last year, Edie Duffy “acknowledges photo-realism is “daggy.”1 I guess similarly I didn't feel very conceptually “cool” at the time.

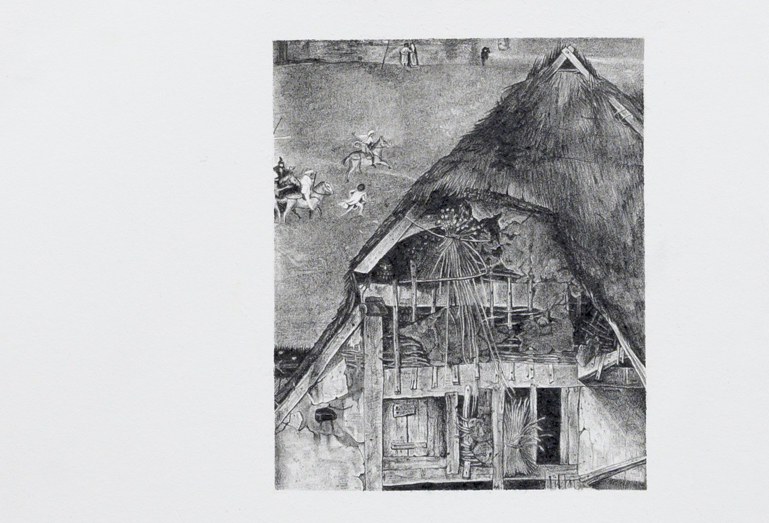

fig.1 Hieronymous Bosch, Triptych of the Adoration of the Magi, Ca. 1494, oIl on oak panel, Mueso del Prado, Madrid.

fig. 2 Translation: Triptych of the Adorationof the Magi by Hieronymus Bosch,ca.1494 (detail) For Ada, 2019,graphite, paper.

I broke my drawing hiatus with two A5 pieces for an exhibition with a friend at c3 Gallery in Abbotsford in 2019. The latter of the two was a small detail from Hieronumous Bosch’s Triptych of the Adoration of the Magi. It was the first in an ongoing lineage of drawing from historical artworks. Pulling source material from places that don't belong to me started in COVID. I was spending a lot of time pilfering national gallery archives to find drawing subjects rather than completing my Library and Information Services TAFE assignments. And it eventually sprawled out to include databases like Wikimedia Commons, The Internet Archive, and many other library and national archive collections.

fig. 3 I love public domain screenshots

fig. 4 tumblr screenshot

It would be negligible to ignore how this practice of collecting and sorting disparate images stems from spending the bulk of my teens in the early 2010s scrolling on the copyright greyzone of Tumblr. I think while a lot of the material I work with comes from or has an air of another time to it, the way I select images and have developed a visual lexicon is deeply informed by a kind of aesthetic curation that came with being on the internet during that time period.

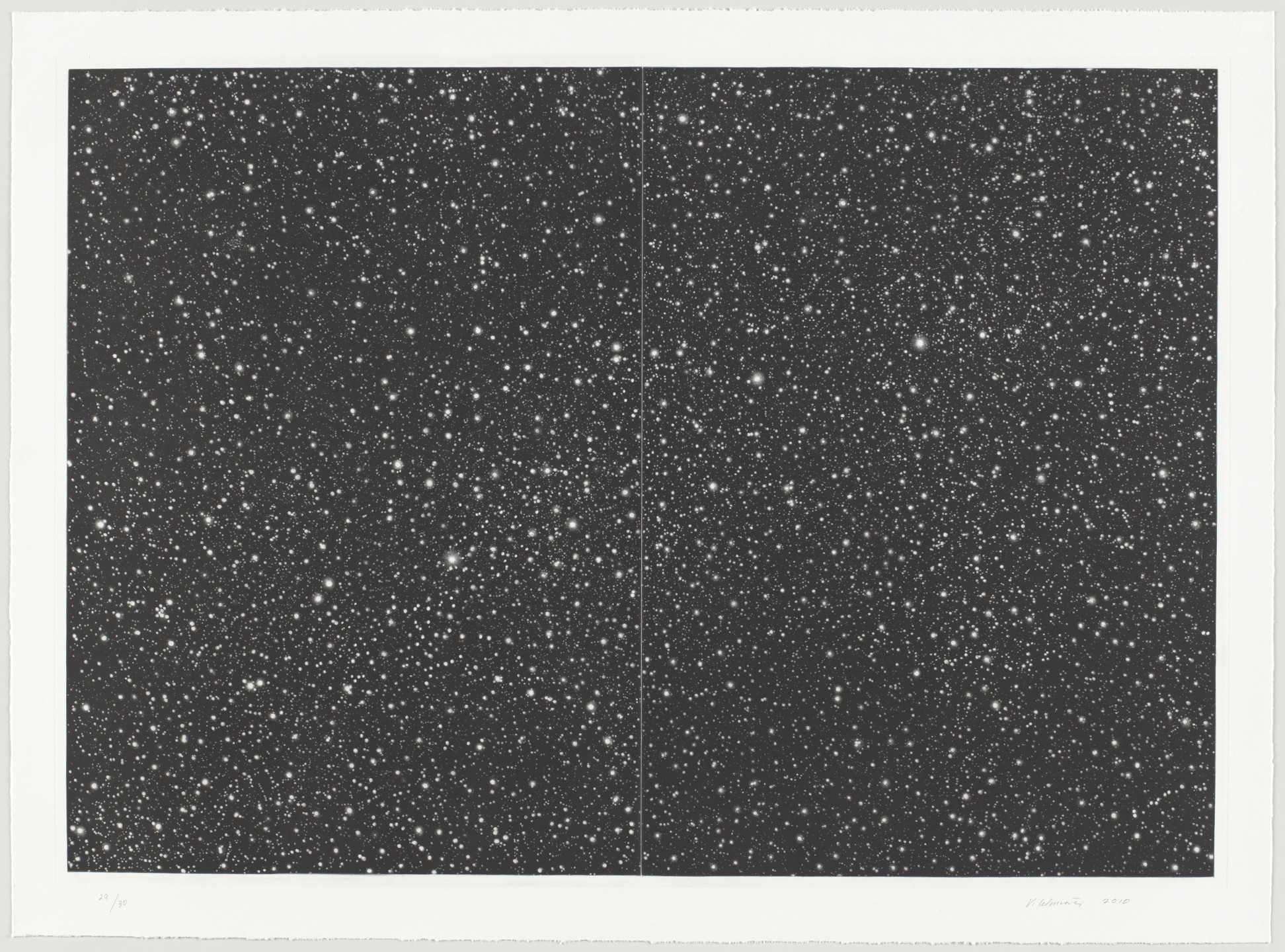

fig. 5 Vija Celmins, Starfield, 2010, Mezzotint and drypoint, MoMA, New York.

fig. 6 Vija Celmins, Ocean, 1975, lithograph on paper, Tate Gallery, London.

In conversation with Latvian-American artist Vija Celmins, American sculptor Robert Gober discusses how Celmins’ later works become deceptive images, no longer are these recognisable renderings of stars and ocean waves the main concept of her practice. Instead, “the paintings seem more a record of [her] grappling with how to transform that image into a painting and make it alive.”2 I like the slow process of translating an image into a drawing, like they are being chewed out for months at a time. Similar to Celmins, when collecting source material I am way more interested in finding the visually similar in images found amongst the deluge of internet collection sites, how drawing can make them alive. Im not as concerned with restricting myself to conceptual continuity.

I’m hesitant to speak too much on this new serries of women in competitive chess and poker. But I started off this series by searching for images of women in sports. Hence the outlier in this series being the child crying in a soccor uniform. I was struggling to find a cohesive collection of images, however I was fascinated by the similarities in the images I was finding of these women playing these games of strategy. These images become like a game or puzzle being reoriented through the process of drawing. This focus on visual similarity, is followed on in my practice of copying and translating historical paintings.

Recently a friend and fellow librarian sent me a document on Information Maintenance as a Practice of Care. It said “If information is to be useful over time, something more than preservation is required: it must be carefully maintained.”3 This library practice of attention and maintenance is reflected in the translation of historical artworks. In drawing, these artworks are maintained and cared for, a slow kind of looking, a maintainance of the library archive.

The practice of copying old masters is a longstanding part of Western artistic education.4 More so than its long standing status though, it's a kind of pedagogy that while incredibly valuable has lost its art school favour with the likes of life drawing classes, kiln firing, and colour theory. Nowadays you hear whispers of drawing departments being seen as the least cool of the fine arts disciplines. Which I think is a shame, especially in a world that is de-skilling and de-literating its people at an astounding rate in favour of automation. We must hold on tight to the artistic knowledge and skills we have, and not forget there is so much to be gleaned from the past.

fig. 7 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres , 'La Belle Ferronnière' (copy of a painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci), c.1802–1806, black chalk, stump & wash on paper, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham.

fig. 8 Léonardo de Vinci, Portrait de femme, dit à tort La Belle Ferronnière, c. 1490 – 1497, oil on wood (walnut), Lourve, Paris.

An example of a prominent master copy is Jean-August-Dominique Ingres’ study of La Belle Ferronnière originally painted by da Vinci in the late 15th Century. In order to prove himself one of the greats of his own artistic generation, Ingres took on the Goliath of a popular da Vinci of the time. Clearly though if one looks close enough at the two versions, you can see Ingres was not content with the efforts of his renaissance master. In black chalk, the face in Ingres’ work becomes more voluptuous, a stronger nose, a more pronounced pout of the lips. And most notably he has paid considerably more attention to the detailed ruffles and embroidery of the lady’s garments.5 I like to see masters studies as a kind of playful forgery. There's something kind of delicious in the tension of testing your skills to see if you can recreate something so challenging. Something satisfying in tending to the information of an artwork, choosing what parts of the original to include or reject. Something important in maintaining of the archive.

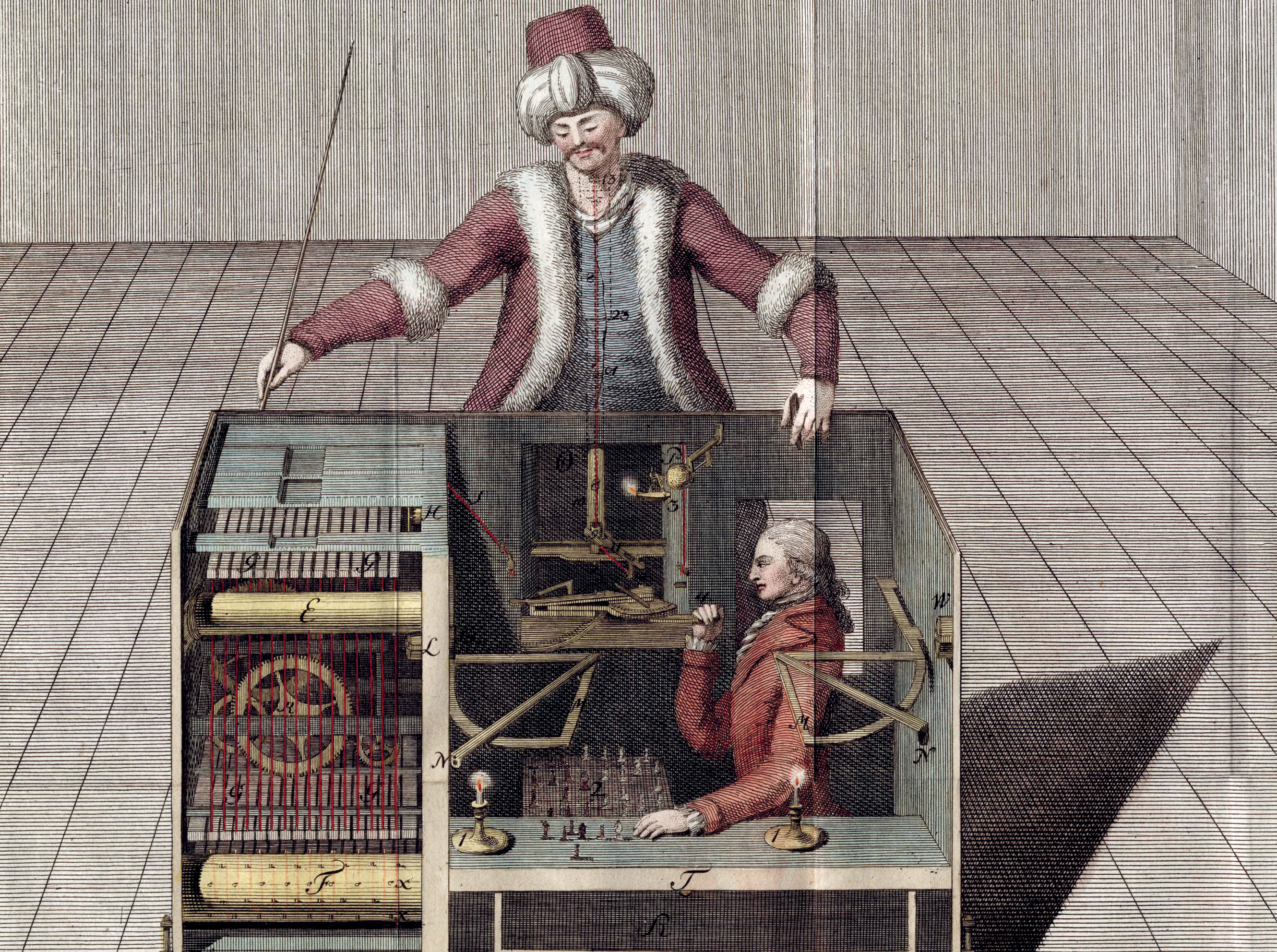

fig. 9 Image of Kempelen's "The Turk", Wikimedia Commons

fig. 10 New York Times and Reddit screenshots

In 1770 Wolfgang von Kempelen debuted the Mechanical Turk, a faux-automaton dressed as a pipe-smoking wizard in Ottoman-style garb, standing behind a large box-like chess table. This early style robot was willing and ready to beat most if not all of its human opponents. Unbeknownst to its gathering audience what appeared as a miraculous machine, utilised hidden doors and mirrors to conceal a human chess master within its chest like table, moving levers and magnets in place of the wizards hand. Though suspected for years it wasn't until 1857, almost a century later that von Kempelen’s hoax was revealed.

Conceived in 2001, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk of MTurk for short, contracted workers from around the world to perform microtasks that allowed the internet function better. Coining the term “artificial artificial intelligence,” Amazon crowdsourced tasks that at the time humans could do much faster than computers. We can see instances of these seemingly automated slippages everywhere from tech giants like Amazon to AI chat bots being puppeteered by engineers in India. The curtain falls, revealing the humanity behind the machine.

Sometimes I feel like a Mechanical Turk. Like a printer. There is always that question of “how do I draw them?” which sometimes leaves me with a kind of amnesia that perhaps I didn't do them at all. That they just appeared. This amnesia hides the slowness that is intrinsic to these drawings, they are chewed out over months at a time. But then if I look closely I can see the parts rubbed away, the intentional inaccuracies from the source material, I can see the hand revealing itself. I like the trickiness of these drawings. They too become like a mechanical chess playing box full of hidden mirrors and doors. That is the beauty of drawing for me, the hand is always there even when obscured from sight.

[This talk was originally presented as an Art Forum at VCA on October 9, 2025 for the exhibition Emergent Fields.]

1 Amelia Winata, “Edie Duffy’s Singularity,” Memo Review, no.2 (2024): 134-139.

2 R.Gober, V.Celmins, “Interview: Robert Gober in conversation with Vija Celmins,” in Vija Celmins, ed. Lane Relyea, Robert Gober, Briony Fer. (Phaidon, 2004),10.

3 The Maintainers, Information Maintenance as a Practice of Care: An Invitation to Reflect and Share (2019), 7, https://themaintainers.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Information-Maintenance-as-a-Practice-of-Care.pdf.

4 George Bothamley, "Why artists copy: a history of drawing the masters," Art UK, March 15, 2024, https://artuk.org/discover/stories/why-artists-copy-a-history-of-drawing-the-masters.

5 George Bothamley, "Why artists copy: a history of drawing the masters."

6 “Mechanical Turk," Wikipedia, October 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mechanical_Turk.

7 "Artificial artificial intelligence." The Economist, June 10, 2006, 11(US). Gale Academic OneFile (accessed October 8, 2025). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A146799488/AONE?u=unimelb&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=dd767161.

8 Streitfeld, David. "How This A.I. Company Collapsed Amid Silicon Valley’s Biggest Boom." New York Times [Digital Edition], August 31, 2025. Gale Academic OneFile (accessed October 8, 2025). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A854140699/AONE?u=unimelb&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=b3f33d7c.